TNQ Writer

There’s nothing quite like coming face to face with a Dwarf Minke Whale on the Great Barrier Reef. Cathrine Best reflects on the moment she gazed into the eye of a gentle giant.

This article was produced in partnership with News Corp Australia.

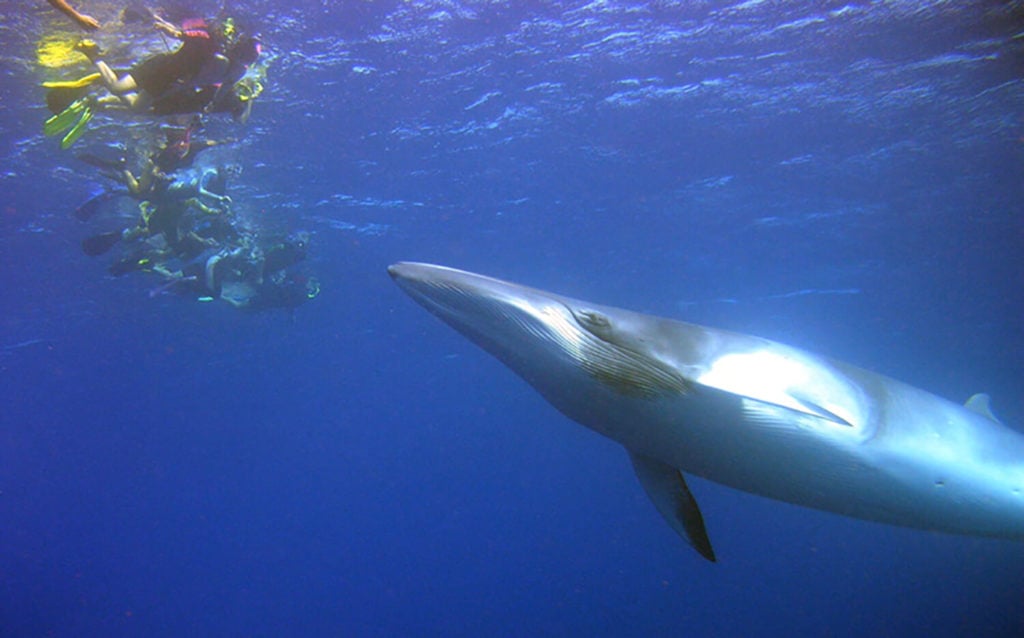

They materialise out of the open water like sea spectres. A rippling shadow, a flash of white, a marbled torpedo fired from the void. I glimpse a flipper, a dorsal fin … and soon I’m gazing into the eye of a whale. She stares back, eye set in a belly button of flesh, so close I can see the pleats along her throat.

For some inexplicable reason, I’m crying. Tears slide down my cheeks and my mask fogs as I shed big, primal sobs. I’m snorkelling with dwarf minke whales on a remote stretch of the Great Barrier Reef and the experience – raw, visceral – has me blubbering.

Perhaps the chop has made me giddy. But if there’s a more humbling experience than staring into the eye of a five-tonne mammal on the world’s largest coral reef, I’ve yet to find it.

My husband, too, would be awestruck. But he’s keeping the home fires burning in the thick of a Melbourne winter; such is the injustice of being married to a travel writer. For me, this is work, and today my office is the Coral Sea and the whales are showing me who’s boss.

I got lucky. My personal and professional passions align. Dr Alistair Birtles – aka Dr Minke – gets it. As head of the Minke Whale Project based at James Cook University in Townsville, he’s spent three decades studying these magnificent creatures. Swimming with them, Birtles explains during our briefing, is an experience unique to Tropical North Queensland.

This is the only known predictable aggregation of dwarf minke whales in the world, so what you are about to experience is very, very special

The second smallest of the baleen whale family (growing up to 8m long), dwarf minkes migrate to Antarctica in summer to feed. But it’s what happens in winter that has research scientists mystified. Every year in June and July they congregate on the Ribbon Reefs, in the northern Great Barrier Reef, and seem to invite human interaction.

That’s why I’m here. To be one of only about 2000 people a season who gets to witness one of the world’s greatest wildlife phenomena.

I’ve joined a three-night cruise with Mike Ball Dive Expeditions aboard Spoilsport, a 30m, twin-hull vessel that accommodates 28 guests in neat, two-berth cabins. It’s essentially a dive boat, with up to four scuba dives (and snorkels) loosely scheduled each day as we cruise south from Lizard Island to Cairns. But when the minkes are out, it’s everyone in – no tanks required.

From the upper sundeck, Birtles – sunhat on, binoculars poised, compass dangling from a lanyard – surveys the sea with the anticipation of a new grandparent outside the birthing suite. We’re looking in vain for a break in the water – a fluke, fin, nose. If there’s a whale here, she’s a slinky minke and doesn’t want to play.

The real minke business comes shortly after sunrise on day two at a dive site known as Lighthouse Bommie. Soon after our 6.30am wake-up call, snorkelling lines are cast off the boat and I gently slip into the water. They’re here. One, two, three – eight minkes. Maybe more.

Mike Ball Dive Expeditions runs 3, 4 and 7 night expeditions to swim with Minke Whales.

They drift in and out of my field of vision, each whale’s approach heralded by a brilliant flash of white. They’re exquisite. Some cruise past at eye level, the crease of their mouths fixed in a quizzical grin. Others approach head-on, sliding beneath me just as I think we’re about to butt noses.

After 90 minutes of watching this mesmerising carousel of whales, I’m numb with cold. I reluctantly pull myself from the water, teeth chattering. Birtles will be in there for a while yet. When it’s time to start the engines, he’s clocked more than two-and-half hours in the water, and the crew pulls him in with the rope line.

The scientist emerges ecstatic, water dripping from his beard, trailing a tradies’ cache of research instruments. He’s met by Julia Sumerling, the on-board photographer, who’s captured a rare moment of a minke gulping (expanding its throat like a pelican), and the image creates a frisson of excitement among the crew.

A Dwarf Minke Whale rises to the surface to say hello

Passengers are encouraged to contribute to the research by taking and sharing their own minke pictures, and their fares also help fund the cause. This year, the season almost didn’t happen. When COVID-19 hit, Mike Ball Dive Expeditions went into lockdown for almost three months, reopening on June 18 – just in time for the minke migration.

While the next season isn’t until mid 2021 (with places strictly limited, booking well ahead is advised), the cruise operator is preparing for a busy summer, fuelled by an expected surge in domestic tourism. Guests can expect to see large aggregations of breeding fish, magnificent corals and even manta rays, which are abundant on the reef in summer, Mike Ball managing director Craig Stephen says.

While summer is our cyclone season, it also offers some of the calmest conditions, allowing us to safely travel to distant locations and to access reefs which, for nine months of the year, are inaccessible because of the weather on the ‘wild side’ of the reef. These calm conditions make for not only great diving but are particularly suitable for the ease of snorkelling

During my expedition, we see between 21 and 26 minkes over three encounters that collectively last more than nine hours. When we disembark, it takes me days to stop rocking. Each wobble taking me back to that quiet place beneath the sea where the minkes dwell.