TNQ Writer

The ancient lava tubes of Undara conceal unique ecosystems and unexpected microclimates. Travel writer Catherine Best can’t wait to return – next time with her kids in tow.

This article was produced in partnership with News Corp Australia.

You’re looking at a section of cave that you will remember until your last breath

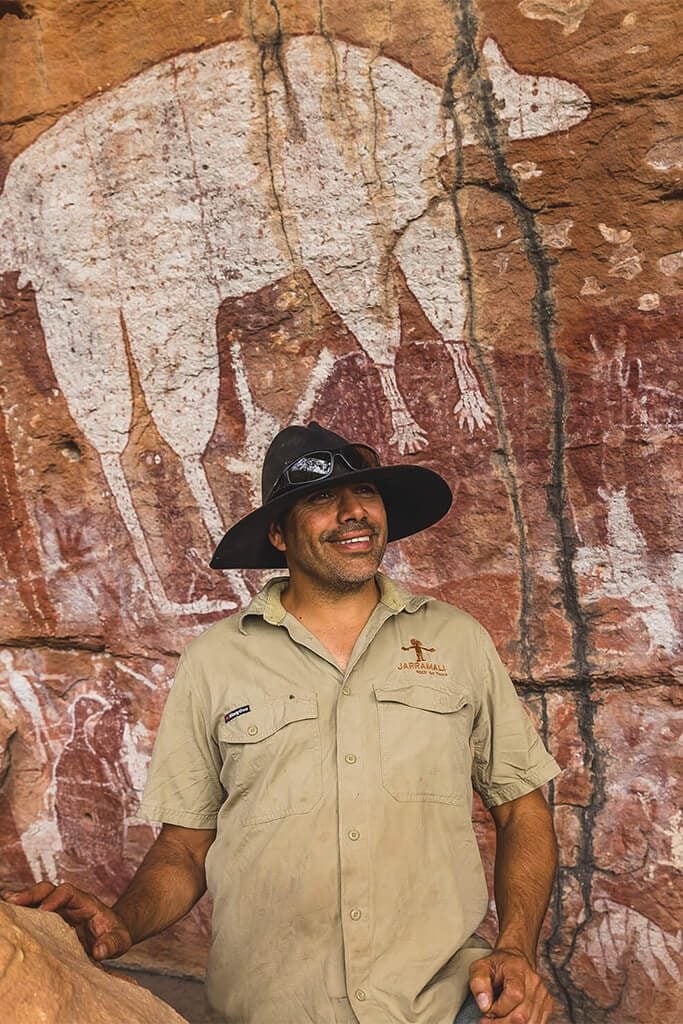

Savannah Guide Bram Collins says. And he’s right. Behind him, a gargantuan chamber rears out of the earth, its cathedral ceiling painted in a mosaic of mineral-rich colours. At the entrance, butterflies dance in the cool air and long vines dangle from centuries-old fig trees.

It’s hard to believe I’m standing in what was once a lava superhighway. When she erupted, 190,000 years ago, Undara Volcano unleashed a sea of molten magma three times the volume of Sydney Harbour. Surging down ancient riverbeds, the lava formed a skin as it cooled and drained, leaving behind what eventually became hollow tubes of volcanic rock.

There are 69 known lava tubes beneath this pocket of north Queensland’s Gulf Savannah Country. Some are 1.8km long, others are as tall as a mid-rise office block. Many are unexplored. This corner of Australia is renowned for its World Heritage-listed reef and rainforest. But one of its greatest natural wonders is underground.

Inside the lava tubes it’s dark and damp. There are spiders, bats and snakes. My kids would hate it. At least that’s what I tell myself as I try to reconcile their absence. As a travel writer, I’ve visited many wondrous places around the globe. But I’m often alone and there’s rarely a significant other to share in the experience.

I have three kids. When I pack my bags for a travel writing assignment, I’m met with sighs and eyerolls: “Where are you going on a work holiday this time, Mum?” This time, it’s particularly tough. Do I tell them the truth? I’m going to be exploring the oldest lava tubes on the planet. I’ll be getting my adventure on like Dora the Explorer. I’ll be privy to a geological wonder so extraordinary Sir David Attenborough says it ought to be declared the eighth wonder of the world.

When I arrive at Undara, four hours’ drive west of Cairns, whiptail wallabies are grazing in the afternoon sun. They look so dainty with their white-striped cheekbones, long eyelashes and gloved paws. My six-year-old daughter would be enraptured. The wallabies startle and bound off behind a row of heritage train carriages. My four-year-old son – a Thomas the Tank Engine tragic – would be giddy with excitement.

All that’s missing is the fat controller. Bram – slimmer and jollier with a touch of the Aussie larrikin – will suffice. A fifth-generation custodian of the lava tubes, Bram is the boss here at Undara Experience, an outback lodge and campsite. When Bram’s ancestors first arrived here in 1861 to graze cattle, they were the northernmost white settlers. Successive generations of Collinses have grown up with nature’s most awesome underground playground in their backyard.

“As a kid I thought if you’ve got a cattle property, you’ve got caves,” Bram says as we set off on a sunset wildlife tour. On the way, a Noah’s Ark of furry friends makes an appearance – eastern grey kangaroos, wallaroos, whiptails – and Bram regales us with humorous fauna factoids. Whiptails have got “mascara going on”, while eastern greys can feed a newborn and mature joey simultaneously. “She can do latte out of one [nipple] and long black out of the other.” My kids would be in hysterics.

At nightfall we arrive at Barkers Cave – an 860m-long lava tube home to a colony of up to half a million microbats. As the daylight diminishes, something extraordinary happens. The adults – no bigger than a thumb – stream out of the cave in great swarms to feed. Waiting for them some nights is a legion of snakes. Bram has seen great wriggling balls of them fighting over prey. Others launch from the treetops, flying through the air in a deadly spiral to snaffle a bat in mid-flight.

We don’t see any snakes tonight. That’s one less entry in the kids’ FOMO ledger at least.

The climax comes when we visit The Archway, Ewamian and Stephenson caves – part of a 164km-long tube system. It’s cooler, greener and thrumming with life down here. This microclimate has a unique ecosystem harking back to the ancient Gondwana rainforests that once covered the entire Australian continent.

I can see my adventurous eldest daughter swinging from the vines like Tarzan’s Jane, unruly tresses collecting leaf litter and cobwebs, a perennial scab on her knee. This is how Bram spent his childhood.

When I saw this for the first time, I was about seven years old; I thought then and I believe now this is probably the most beautiful thing I’ve ever seen.

We venture into Ewamian first, following Bram’s torchlight into the abyss. I’m silent. Taking it all in. Stephenson is next. Then I see it, our snake. A spotted python unfurling its scaly coils in the sun. I’m the worst mum in the world. When COVID travel restrictions allow it, I’ll be back. With the kids and a dilly bag full of marshmallows.